Genealogy Tips in County Mayo

The best you can do if you wish to trace back your family tree is to commit yourself to dedicated centres.

Staff can access the databases of all resources and find the right records for fulfilling your research.

However here are some tips that might help you on getting started the preliminary research by yourself.

SURNAMES

Surnames commonly associated with the county include Walsh, Burke, Gibbons, Prendergast, Joyce, Murray, Gallagher, Lydon, Heneghan, Jennings, Feerick, Langan, Murphy, O'Malley, Kelly, Moran, Duffy, O'Connor, Waldron, Farragher, McNicholas, Brennan, Kelly, Loftus and Keane.

Many Irish surnames can be distorted over the centuries and have different spellings. The Irish population used to speak Irish as the first language, and the English speakers record keepers pseudo-translated, transcribed phonetically and transposed surnames into ones that sounded more English.

Also, the prefixes ‘O’ and ‘Mc’ meaning “grandson of” and “son of” were often omitted before the 20th century. For instance, Mc Mahon became Mac Mahon, Mahon or even Mahen, Ó Brolcháin became Bradley; Mac an Bhreithiún (son of the judge) became Judge, Breheny, Brehan and O’Reilly became Reilly (or Riley, or Rily, or Riely). Only with the Gaelic Revival at the end of the 19th-century surnames had back their prefixes.

PLACE NAMES

In Ireland, loyalty to a place of origin is still strong and leads to the existence of a large number of townlands and parishes. Each of them has traditional place-name lore and stories.

To this day the more than 60,000 townlands are still the basis of rural addresses.

Place names have evolved and deformed over the centuries.

In 1800, following the Acts of Union, the administration of Ireland passed to England de facto.

Measuring the country and valuing properties as a basis for an effective taxation system was one of the first objectives and in the 1820s the Ordnance Survey was launched.

The Ordnance Survey standardised the spelling of all rural place names from the Irish language into English, mapped and set administrative boundaries and assessed the productive capacity of all property.

CHURCHES RECORDS

Church Records and Parish Registers are an excellent source for searching ancestors.

Records include baptisms, marriages and sometimes deaths/burials for all classes of the population and many details of daily life, kept by priests and vicars, can be found.

They can give information before the introduction of civil registration in Ireland set up in 1864.

Roman Catholic

Roman Catholic registers are kept in the individual parishes and, the recording of baptisms and marriages can vary widely from parish to parish.

Often they are very complicated to read because names and addresses were not standardised and sometimes the complete records of a family can be found in parish registers of nearby villages or counties due to frequent moving at that time.

Church of Ireland

Registers of the Church of Ireland are easier to research, comparing to the Roman Catholic ones because it had a more regular system of recording entries and used formatted books.

Unfortunately, the fire at the Public Record Office in Dublin during the Irish Civil War in 1922 destroyed the most of the Church of Ireland registers and, nowadays local rectors hold the existing parish registers.

CIVIL RECORDS

Civil Records give information about births, marriages and deaths.

From 1864 onwards official registration of all births, marriages and deaths were set up in Ireland.

A birth record of an individual contains date and place of birth, child’s name, surname, address, the occupation of father, mother’s maiden name and details of the informant.

Marriage record provides date and place of marriage, the names of groom and bride, their ages, current marital status, occupations, addresses, fathers’ names and fathers’ occupations.

Starting from April 1845 all Non-Catholic marriages were registered.

A death record gives little information about name, age, marital status and occupation of the dead person, the place and cause of death.The name of the informant, usually a relative, can also be found.

CENSUS RECORDS

In Ireland, the first census was undertaken in 1821 and from that year onwards every ten years until 1911. The 1921 census was not conducted because of the War of Independence.

In 1926 the population of the Irish Free State was recorded for the first time. After the World War II, the censuses were undertaken around every five years.

In censuses, information about the name of the householder and the occupants of the house on the day the census, age, religion, occupation, place of birth of each person and relationship to the head of household can be found.

Also, indexes can include records about territorial divisions, town, townland, streets, civil parish and District Electoral Division.

Unfortunately, many census returns were destroyed, and only a few survive today. The most of 1821, 1831, 1841 and 1851 returns were lost in the fire at the Public Record Office, the Four Courts, Dublin during the Irish Civil War in 1922, while 1861, 1871, 1881 and 1891 returns were destroyed by the State.

CENSUS SUBSTITUTES

In many Irish parishes, church registers appeared only after 1800.

For this reason, searching family connections can be quite difficult back through the 17th and 18th centuries.

There are some sources referred to as census substitutes covering the 18th century and earlier.

-

Flax Growers’ Lists 1796 (list of farmers who grew flax)

-

Religious Census 1766

-

Protestant Householders Lists 1740

- Hearth Money Rolls 1663 (tax for every fireplace in a house)

In these sources, only heads of household are listed. There is no information about family members.

LAND RECORDS

Griffith's Valuation, carried by Richard Griffith, was a boundary and land valuation survey of Ireland completed in 1868. It covers all records over the period 1848 and 1864.

It helps to identify the ancestors’ place of origin and parish. Each record gives information about the name of occupier, the name of leaser, County of residence, Barony of residence, Parish of residence and Townland of residence.

Sometimes street, subdivision, description of property, acreage and valuation can also be found.

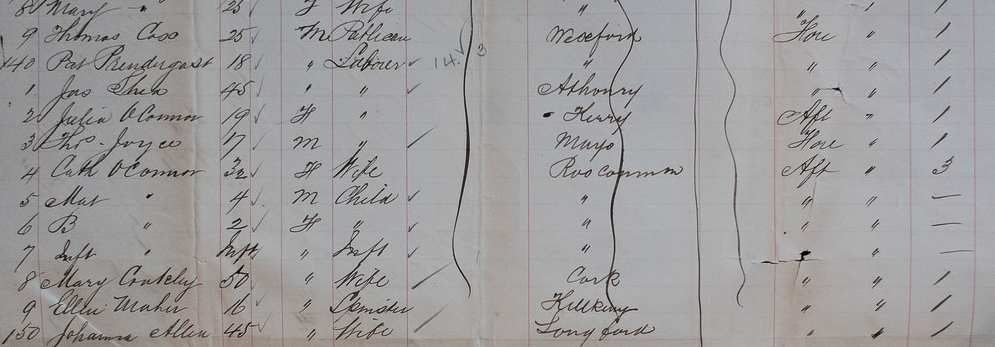

SHIPS’ PASSENGERS LISTS

Reading through the ship passenger lists can help ancestors’ research.

Some databases have more than 4500 transcriptions of lists dating from 1791 to 1897. The records belong to ships that left from Irish and British ports to ports in Us (often New York or Ellis Island) and Canada.

The records contain a combination of information such as name, sex, age, birth year and country, occupation, ship name, ship departure port, arrival year and date and arrival city and the bulk of them coincides with the Great Irish Famine.

Sometimes more additional information can be found about passengers: writing and reading skills or language; but also what part of the ship they were assigned.

Many surnames of passengers were of Irish origin. Often passengers were related each other.

GRAVESTONE INSCRIPTIONS

Gravestone inscriptions can give information about birth, marriage and death of a person or his family members if they are buried in the same grave.

Sometimes information about the occupation or possible military service can be read on the gravestone.

Before 1864 the civil registration of death was not in existence, and only small amounts of parish death or burial records were registered so that gravestone inscriptions can be a useful source.

It must be considered that sometimes gravestones were erected many years after the deaths by distant relatives and may give inaccurate information and low-income families, such as peasants or farmers, couldn’t afford inscribed gravestones.

NEWSPAPERS

Newspapers are a precious source of information.

Often national newspapers used to publish information which came directly from the regional press, giving access to local news.

Local newspapers provided them not only announcements of births, marriages, and deaths, but also legal notices detailing the settling of estates and land sales, and advertisements.

Also, newspapers received information about national and local events described with the point of view of the contemporary community such as the Great Irish Famine or Fenian Risings.

At that time the most popular Mayo’s newspapers were:

-

“The Telegraph" or "Connaught Ranger" ( 22/9/1830-13/05/1876, nowadays "Connaught Telegraph") based in Castlebar

-

“Mayo Constitution" (3/1/1828-18/11/1871) based in Castlebar

- “Tyrawly Herald"(25/1/1844-1/9/1870) based in Ballina.

County Mayo

A large number of records relating to County Mayo can be found including:

Baptismal/Birth Records 580,487

Marriage Records 219,222

Burial/Death Records 126,024

Gravestone Inscriptions 53,279

Census Records 400,953

Griffith's Valuation 47,286